Saprea > Online Prevention Resources > Prevention Resources: Support

Supporting is about helping your child work through ups and downs, guiding them to identify emotions, and creating safe spaces for them to share their thoughts and feelings.

We recommend that you Support by:

Emotion Regulation

Coping Strategies

How Is Emotion Regulation Related to Sexual Abuse Prevention?

Self-Compassion

Empathy

Reduced High-Risk Behaviors

With the goal of building empathy in children in mind, it’s the perfect time to consider that impulsive behaviors may arise out of a desire to numb or distract from strong emotions. In other words, a child —even your child—may behave in a way that is out of character for them when they are overwhelmed by feelings that they don’t know how to manage. When these overwhelming feelings cause a child to feel like everything is out of their control, they may attempt to create areas of their lives that they believe they can control by turning to substances, bullying, or other antisocial or high-risk behaviors.

This can also manifest as a child or youth causing sexual harm to another child, something that may create detrimental and long-term impacts for both children, but especially for the child being acted upon. In fact, research indicates that in over half of reported cases of child sexual abuse, the survivor was abused by another minor.1 In part, this is why we advocate for teaching kids about empathy, especially in partnership with principles of consent. Our goal is that with a better understanding and willingness to practice empathy, and to respect the boundaries and wishes of another, there will be fewer instances where sexual abuse is the result of the actions of another child or minor.

Helping your child learn and increase their ability to regulate their emotions is something that will take time and isn’t something you’ll be doing alone. They’ll learn strategies from observing other trusted adults, interacting with siblings, and during play with friends. You may even choose to work in tandem with a therapist who can help your child learn coping strategies and be an additional outlet for sharing and processing. Your willingness to talk about, tend to, and advocate for their emotional well-being can strongly contribute to their belief that you are one of their go-to, trusted supports.

How Can I Teach My Child to Cope with Their Emotions?

Emotion regulation isn’t something we’re born with. Babies depend on caregivers to provide comfort and reassurance, sometimes through meeting physical needs, and other times through soothing touches or reassuring sounds. As babies grow into toddlers and then older children, they learn their own ways to self-soothe and relax themselves, doing things like rubbing a blanket on the tip of their nose, twirling their hair, or rocking back and forth. Over time, they’ll need to develop additional strategies to manage big emotions, and you’ll be a central part of that learning.

It may feel overwhelming to think about being a model of emotion regulation for your kids, and you’re not alone if that’s what is coming up in your mind right now. This is another great time to circle back to self-compassion, with a reminder that you’re going to get things wrong —maybe even a lot of things wrong—and that’s a very human thing to do. Your humanness creates a great opportunity to show your child what self-compassion looks like, to offer apologies where needed, and to course correct when you realize you’re coping in ways that don’t align with your values.

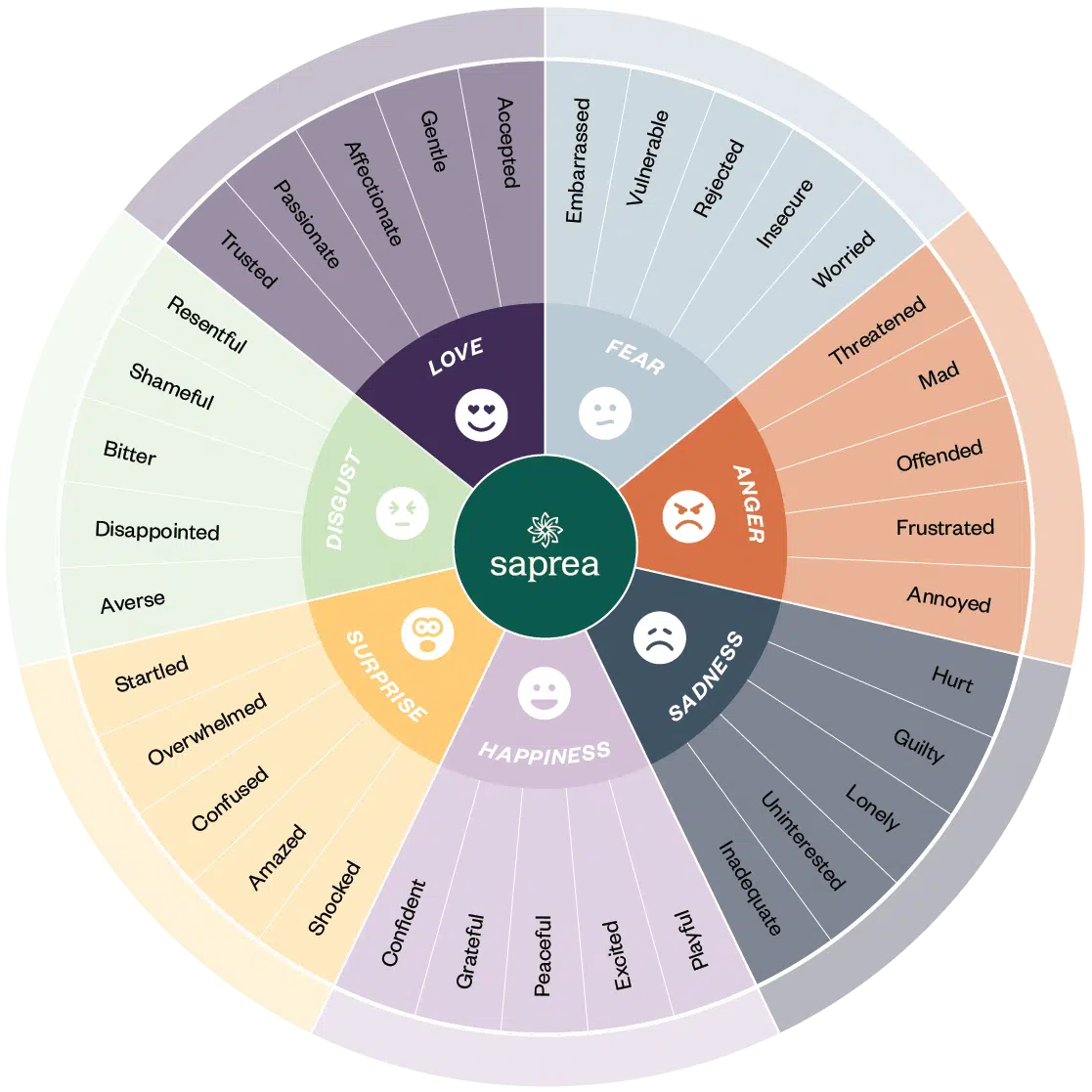

Emotion Wheel

Learning to cope with emotions requires patience and practice, for you and your child. A great place to begin is by naming the emotion that your child is feeling. Our emotion wheel can be a helpful resource for your child to find words to describe what they’re experiencing.

You can invite your child to identify the emotion (or emotions) that feel the closest to what they’re experiencing. Then, help your child notice how different the emotion(s) is experienced in their bodies. They may feel shaky, flushed, have a fast heartbeat, butterflies in their tummy. You can help them understand how the emotion impacts how their body feels. Then, take three deep breaths together and pause to notice how the body feels after the breaths. It can be empowering for a child to understand that they have influence over their body’s physiological responses to various emotions. And, as you help them become more connected to and aware of the emotions they’re experiencing, you may find that you’re more aware of your own feelings.

Activities to Express Emotion

Movement

Exercise has benefits to bodies of all ages, and movement can be a great way to cope with emotion. But not all movement has to be sports or fitness related. Use the emotion wheel (above) to serve as the prompt for a dance party, with a full minute dedicated to doing a happy dance, then a sad dance, an angry dance, followed by a calm dance. Not only is movement like this great for the body, but it also communicates to your child that it’s okay to feel emotions, and there are great ways to process emotions that don’t involve doing anything destructive or hurtful.

Art

Artistic expression through painting, drawing, or music can also be a powerful way of acknowledging and processing emotion. You and your child may enjoy drawing or coloring lines to depict what anger or excited feels like. If your child plays an instrument, they may find that playing parts of a song in a way that matches how they feel inside can be cathartic. There are some adults that still pound away at the piano when they’re feeling frustrated—it’s wonderful!

Mindfulness

How Can I Help My Child Be More Confident?

It happens so fast: one minute your toddler is dancing and singing without inhibition because they don’t have any concept of someone being critical of their voice, their dance moves, or anything else. And then the next minute, they come home from school broken-hearted because their best friend in the whole world made a disparaging comment about their new glasses. Where confidence was once the rule, now you’re keenly aware of the need to help your child rediscover and hold onto their intrinsic value.

Feeling capable and supported can build confidence. It’s difficult to place value in your ability, or potential ability, if you’re convinced that the ability doesn’t exist. You likely know what we’re referring to because low self-confidence isn’t just a kid thing; as adults, we have our challenges with believing in ourselves, too. If you’re concerned that your child’s confidence is persistently low, there are things you can do to boost it.2

01

Model It

02

Allow for Mistakes

Fear of failure can prevent a child from trying. Nurture an environment in your family that allows for mistakes to be something from which your child can learn. The spilled plate of food can be an opportunity to learn to use a mop; the sibling fight can be a chance to talk through how they each might adjust actions in future situations; the dent in the car an opportunity for your teen driver to labor alongside you in the yard to work off the cost of the repairs. Whatever the mistake, the important part is that the past isn’t the focus, but instead how it can be a catalyst for growth.

03

Balance Challenges with Successes

Your child may gravitate to and stick to one thing they’re good at, or they may bounce around from thing-to-thing without giving themselves enough time to develop skills. Giving them an opportunity to do something that’s well within their abilities is rewarding. And, providing encouragement, support, and praise as they stretch to try something new may provide a big boost of confidence. Having a balance of both helps to reinforce the idea that being good at something is great, and being willing to try something new is as well—even if it doesn’t come easy to them.

04

Count on Contributions

You may have noticed that, as an adult, having a sense of purpose goes hand in hand with feelings of contentment, joy, and well-being. The same is true for children. Feeling wanted, needed, and valued can help strengthen their confidence in what they can contribute and how they can positively impact others. You can help nurture this sense of confidence by assigning your child responsibilities around the house and rewarding them when those responsibilities are carried out. When your child feels like they are making a difference—like their contributions matter and others are counting on them—they are not only more confident in their capabilities, but also more motivated to utilize and strengthen those capabilities.

05

Listen

One highly effective way to help your child feel loved, appreciated, and seen is by listening to them. If they feel that you are genuinely listening and invested in what they have to say, then they will be more assured that their voice matters. For instance, you could invite them to express their views on family decisions, such as household boundaries around internet use. Offering your child these opportunities communicates the message of, “You have important ideas to contribute, and I care what you think.” Actively listening to your child also helps to build trust, reinforcing that they can come to you for anything, no matter the topic, challenge, or concern. With this confidence in not only their own voice, but in you as a trusted source of support, your child will be more likely to seek out help, even if they feel ashamed or have been pressured to keep quiet.

06

Spend Quality Time with Them

Odds are your child is aware—even if on an unconscious level—just how busy you are and how important your time is to you. When you make the effort to engage in one-on-one activities with your child on a consistent basis, you are communicating that they are someone worth spending valuable time with. This is especially true when you tailor this time to their specific hobbies and interests, demonstrating that what they care about is inherently important. Whether it’s going on a bike ride, visiting the library, doing a puzzle, or playing your child’s favorite video game or sport, one-on-one time validates to your child that they are deserving of your time, attention, and interest.

How Is Shame Related to Child Sexual Abuse?

Emotion regulation and increased confidence can also help your child navigate through one of the most difficult emotions we all experience—shame. Shame is a deep sense of unworthiness for our own existence.3 When we feel shame, we can experience a range of symptoms, including feelings of worthlessness and failure, negative self-beliefs, and a desire to hide or isolate from others. Shame can even impact us physically, perhaps causing pain, nausea, or other distressing sensations in our bodies. We may feel an urge to disappear, make ourselves smaller, or sink through the floor.

Given how intense and debilitating shame can sometimes feel, it’s easy to see how a child can feel overwhelmed by or “stuck” inside the emotion. Without the proper tools and support to manage it, a child who experiences persistent feelings of shame may become more vulnerable to other harms, such as child sexual abuse.

Sadly, shame and child sexual abuse are often intertwined. This is because shame is both a risk factor and a potential outcome of such abuse. For example, if a perpetrator notices that a child frequently experiences shame, they might seek to groom the child by offering relief, comfort, or an escape from that shame and other distressing emotions. A perpetrator may also exploit the child’s shame to keep them quiet about the abuse. They may reinforce the child’s fears with statements like, “No one will believe you,” “They’ll think it was your fault,” or “Your parents will be even more disappointed in you than they already are.” The child may also try to make sense of why someone would hurt them by filling in the gaps with conclusions like “I’m not worth protecting,” “I did something to cause this,” or “This is the type of love I deserve.”

Where Shame comes from

As powerful and painful an emotion as shame can be, reducing the shame your child feels can make all the difference in not only lowering the risk of abuse but empowering them to come to you if something does happen. So how can you help to reduce your child’s feelings of shame? First, it can be helpful to understand where shame comes from and how it affects us. Shame, like emotion regulation, is not something you are born with. Rather, it’s something you learn through your interactions with others.

According to researcher and physician Gabor Maté, shame often first develops when a parent scolds or disciplines a child. This interaction might happen in a moment of panic when you want to protect your child from immediate harm. Picture your child reaching up to touch a hot stove or running out into the middle of a busy street. In such moments, you may shout, grab their arm, demand that they listen to you, and display feelings of great distress. These responses are natural—even necessary—to communicate danger. However, as justified as your actions are, your child may feel shame as a result. They may not fully understand why you got so upset. And, to fill in the gaps, they may jump to the conclusion that they are the reason, rather than their actions. They may think “I am bad,” rather than “I did something bad.”

Reduce Shame with Repair Work

It’s important to pause here and keep a couple things in mind. First, you are only human and doing the absolute best that you can. No parent can respond calmly and mindfully to every situation all the time, no matter how many breathing techniques you practice. Second, these interactions between parent and child are natural, inevitable, and universal. It’s impossible to raise a child and not have these moments of miscommunication and disconnection occur.

The good news is that you can significantly reduce or alleviate that shame by the repair work that follows these negative interactions. “Repair work” in this context refers to the actions you take to mend the hurts that your child may have experienced. This typically involves allowing yourself the time and space to calm down, and then reaching out to your child to discuss what happened. In these conversations, you can acknowledge and take ownership of your big emotions in that moment and calmly discuss with your child why you spoke the way you did. You might acknowledge you made a mistake and apologize for your behavior. In other cases, you might clarify that you were upset by your child’s actions, not with them as a person. These clarifications help guide your child’s understanding toward “I did something wrong” and away from “I am something wrong.” As Kristin Neff, a leading expert in self-compassion, puts it:

Whatever the situation, parents don’t leave it up to their children to do the repair work after the interpersonal bridge has been broken. If left to them, the child will likely internalize shame, which will snowball over time, being reinforced over and over again by future interactions. Instead, as the parent, it’s your responsibility to do the follow-up work and have reconnecting conversations to mend the bridge. As you do so, your child’s shame is reduced as they understand that they are not inherently a bad person. They leave the conversation feeling reassured and reconnected, knowing that they always have your love and support, even when they make mistakes.

It’s not just your child who feels empowered by these moments of reconnection. As a parent, it can be encouraging to know that while you cannot control or prevent these breaks in the interpersonal bridge, you can control your contributions to the repair work afterward—repair work that reduces shame, strengthens trust, builds communication, and teaches your child that making mistakes doesn’t change how much they are loved and valued.

Teaching Your Child Self-Compassion

Speaking of feeling loved and valued, another fantastic way you can help reduce your child’s shame is to nurture their self-compassion. Self-compassion is actively loving and valuing yourself for who you are right now. Not who you’ll be a month from now, or who you’ll be when you check off all your New Year’s resolutions. Rather, self-compassion tells you it’s okay to acknowledge your flaws and challenges because suffering and imperfection are part of the human experience. If all of that feels a little daunting, that’s okay. Self-compassion can sometimes seem difficult, even impossible, especially when you consider how easy it is to be hard on yourself. It doesn’t help that your inner critic is all too eager to point out all the things you’re doing wrong and all the ways you’re falling short. Self-compassion, on the other hand, is about offering yourself the warmth, kindness, and empathy you would offer a friend if they were in your shoes.

Thoughts of Kindness

Resilience

Common Humanity

Along with modeling self-compassion and allowing room for mistakes, another excellent way to nurture your child’s self-compassion is teaching them about common humanity. Often when you feel shame, you have thoughts like, “Everyone else is fine, I am the only one struggling with this,” or “Why can’t I be as happy as everyone else?” These thoughts can create feelings of disconnection, isolation, and loneliness. Common humanity, on the other hand, encourages you to see how your individual experiences connect to the experiences of others. It helps you recognize that you aren’t alone—that suffering, failure, and imperfection are all part of the shared human experience. When you have this realization, you not only feel more connected to others, but you feel more compassion toward your own struggles.

Reminding yourself that everyone suffers sounds simple enough, but you can probably see how this pattern of thinking might not come naturally for everyone, especially children. After all, with their still-developing brains, children often see themselves as the center of the universe. This, combined with their incredible ability to wallow, can make every distress or concern feel catastrophic. An embarrassing moment at school feels like the end of the world. And a bad day isn’t just a bad day, but the worst possible day that anyone has ever had.

When your child is experiencing a challenge or difficulty, their go-to response is likely, “No one else knows what I’m going through. Something this bad has never happened to anybody but me.” It’s in these moments that you can teach your child common humanity. While working to not minimize or invalidate their concerns, you might explain that they aren’t alone, that many others know exactly what they’re feeling, and that what they’re going through is part of being human. Another wonderful thing about common humanity is that it strengthens your child’s compassion not only for themselves but for others. This ties back to fostering emotion regulation and empathy described above.

As you provide reassurance, comfort, compassion, and model healthy ways to experience and cope with emotions, you will likely feel increased connection with your child. And it’s this connection, along with your continual involvement as the incredible parent you are, that will help your child feel supported. It will bolster their sense of identity, belonging, and worth. They will know that they are loved, that they are allowed to make mistakes and feel big emotions, and that they are capable of immense growth, compassion, and resilience.

Continue Learning How to Prevent Child Sexual Abuse:

Educate

Monitor